Legalism vs. Confucianism in Procurement: Presumption of Guilt or Innocence?

- ukrsedo

- Jul 18, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Jul 18, 2025

Legalism and Confucianism

Legalism and Confucianism, two contrasting schools of ancient Chinese thought, suddenly resonated for me in the procurement context.

These philosophies were initially intended for governmental development, so their principles map well onto procurement ethics and governance.

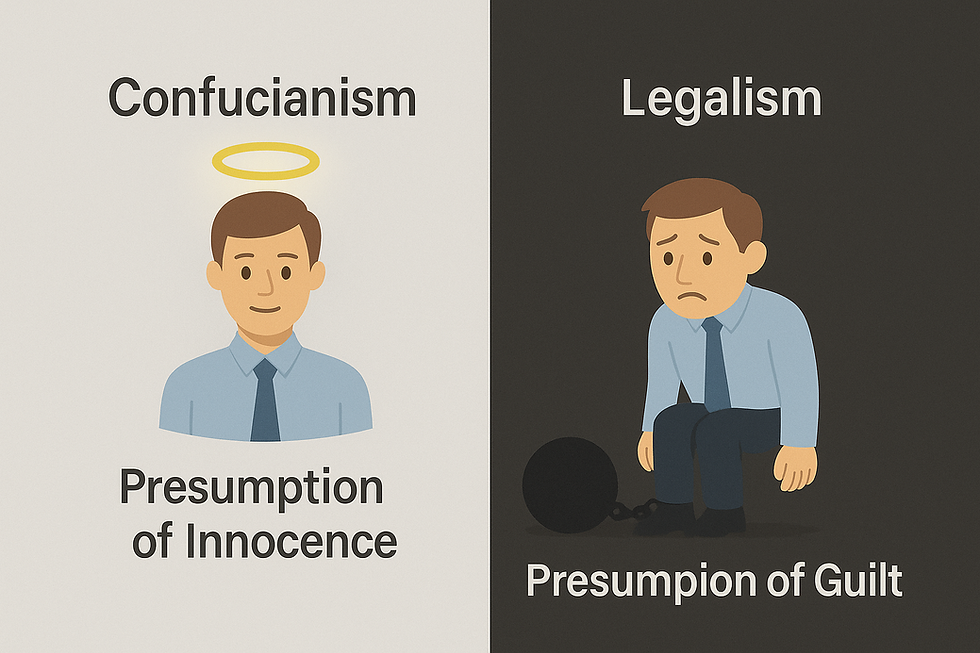

Legalism assumes that individuals are naturally self-interested and prone to misconduct unless controlled by a strict framework of rules, punishments, and incentives.

In procurement, this manifests as presumption of guilt: buyers are required to demonstrate compliance, justify decisions in detail, and operate under layers of approval and audit.

In contrast, Confucianism focuses on morality, virtue, and the cultivation of personal ethics, leaning toward a presumption of innocence.

Here, procurement professionals are trusted to act in the best interest of the organisation, guided by a strong moral code and professional standards rather than fear of punishment.

Which Presumption Prevails?

In today’s global procurement landscape, Legalism dominates, particularly in the public sector and regulated industries.

Complex compliance frameworks (e.g., anti-corruption, ESG, various auditing entities and functions) require buyers to prove that every action is fair, transparent, and duly recorded.

However, many leading organisations are now shifting (or pretending to) toward a hybrid model that combines strong ethical principles with leaner controls, enabling agility, innovation, and supplier collaboration.

This embraces a Confucian mindset, but still falls within the Legalist guardrails.

Coloured Organisational Models – Two Extremes

Laloux’s “Reinventing Organisations” offers a colour-coded framework that mirrors this Legalism–Confucianism tension.

Red and Amber companies (authoritarian or rule-bound) reflect a Legalist structure, characterised by centralised decision-making, rigid hierarchies, and strict control over buyer behaviour.

Procurement in such organisations is often reactive and transactional, with buyers acting more as compliance officers than value creators.

Green or Teal organisations, on the other hand, emphasise trust, empowerment, and self-management, closer to a Confucian ethos.

Procurement in such companies operates with high autonomy, guided by values and purpose rather than just rules. Buyers are expected to exercise judgment, act ethically, and collaborate with suppliers to achieve long-term goals, rather than “tick the box” on compliance.

In some companies, this philosophy becomes destructive. Then, decisions aren't being made due to a lack of stakeholder consensus, which prevails over business and common sense.

In reality, most procurement organisations exist between these extremes, often oscillating depending on external pressures (e.g., compliance breach scandals push companies toward Legalist rigidity, while growth and innovation cycles favour Confucian trust).

Mechanistic vs. Organic Procurement (Burns & Stalker)

The Burns and Stalker framework provides an additional lens for examining procurement governance.

Mechanistic structures, with their rigid hierarchies and standardised processes, align closely with Legalism. Such environments are effective in stable, predictable markets where compliance, risk management, and cost reduction are the primary focus. Buyers are narrowly defined in their roles, with limited scope for judgment or creativity.

Organic structures, by contrast, thrive in dynamic, uncertain environments — much like Confucian thinking. Procurement here is adaptive and collaborative, with cross-functional teams, empowered decision-making, and flexible processes.

For example, technology companies that source fast-evolving SaaS platforms or AI tools often operate in an organic mode, where trust and strategic partnerships matter more than procedural compliance.

The challenge is finding the right balance: overly mechanistic procurement struggles with agility, while overly organic approaches risk governance gaps. Hybrid operating models — structured yet adaptive — are increasingly becoming the best practice.

The U.S. Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) is a remarkable benchmark because it embodies both Legalist and Confucian principles.

On one hand, FAR is rule-heavy, prescribing detailed procedures to ensure fairness, transparency, and accountability in public procurement. It mandates documentation, competition, and conflict-of-interest controls, clearly reflecting a presumption of guilt (or at least caution).

Yet FAR in "1.102 Statement of guiding principles for the Federal Acquisition System" provides significant room for “personal initiative and sound business judgment” by contracting officers and buyers. It explicitly states that contracting officers are responsible for “ensuring that contractors receive impartial, fair, and equitable treatment” while exercising their initiative and judgment to achieve “best value” for the government.

I wish this becomes the first article of anyone's Procurement Policy.

Integrating Theories for the Future of Procurement

Procurement today is too complex to rely solely on Legalist or Confucian approaches. Yet, the procurement presumption of guilt must vanish like a repelling anachronism!

Companies are increasingly adopting principles-based governance, establishing broad ethical and strategic principles alongside rules-based compliance for high-risk areas.

Burns and Stalker’s organic vs. mechanistic dichotomy is particularly relevant as procurement evolves. Digital tools (S2P platforms, AI analytics, and supplier risk apps) allow for automation of repetitive, rule-bound tasks, letting buyers focus on strategic, organic, and relationship-driven activities.

In this sense, procurement is digitally evolving from a mechanistic compliance function to a source of value and creativity.

Forward-thinking organisations are fond of “Teal Procurement” — a self-managing, purpose-driven corporate function that demonstrates the virtues of ethics and agility.

By three methods we may learn wisdom: First, by reflection, which is noblest; Second, by imitation, which is easiest; and third by experience, which is the bitterest. Confucius

Comments